Robertson Davies, What’s Bred in the Bone

While Kit waited for the windfall gift for Roger, the little judge himself was trying to manage his last days. At Chalk church, Father Lawrence had said yes, so the next morning Roger spoke briefly to those assembled, announcing that on December 10th there’d be a commemorative service for Sir John Oldcastle, a service to which neighboring congregations would be invited.

|

| Roger Manwood |

Later that morning Roger set off for Canterbury on his black stallion, his house steward Jack Fisher riding beside him. They cantered easily to Rochester, crossed the bridge and trotted on toward Sittingbourne, Roger studying the familiar surroundings, hurrying along without talking. He had decided he’d tell no employee or family member about the execution. He’d say a vague goodbye at home, settle things with Archdeacon Redman, ride back to Shorne and go it alone on the fourteenth, unless Redman insisted on being present.

As the two horsemen negotiated the wintry highway, Manwood thought back across his life. He’d lost his ears on a move for Princess Elizabeth against the Edward Seymour protectorate then in power. After Elizabeth worked her way to the throne, he’d been right-or-wrong loyal to her friends and policies, year after slogging year. Sir Tom Gresham, and at first Archbishop Parker, had been true friends — he’d been legal counsellor to them both and Parker’s land-steward. 1

But the queen’s liberality toward protestants faded as her harshness toward Catholics grew; the Anglican settlement was her refuge — in the middle, she said, there was something for all. That the Anglican church itself was part protestant in Catholic clothes should, she believed, reconcile every one of her subjects. Roger’s work became difficult – and in May ’73 came a blot on his soul he’d been trying to erase: in a commission with the bishops of London and Rochester he’d allowed the conviction of two Flemings as anabaptists, and held still while the bishops burned them alive. 2 He still dreamed of that day, and when he was placed on the ecclesiastical commission the following year he vowed to himself never to allow such cruelty if he could stop it. He’d done a lot of blustering from the bench about possible hard-line sentences but at the end managed many a release for harmless defendants – that is, until Whitgift came to power in ’83.

Thinking back, it was Whitgift who became the symbol of evil in Roger’s mind. Every aspect of the man – his cruelty, his insistence that his lawless will be done, his insidious power over the queen – flaunting the law of praemunire by mixing church with temporal power – pushing his way to the head of the table in privy council.

Roger slowed his big horse to a walk, reined him around an icy puddle. It was Whitgift who’d stirred Roger to create Marprelate. Most of the other bishops exhibited cruel frailties, sure enough, but Whitgift was the poisoner who had to be revealed in print – the man who could spoil England’s government – who would spoil it, Roger thought gloomily, if allowed to persist. Maybe not in the man’s own lifetime, but he’d already made the cracks – they were showing – despotic methods, pulling apart the house of English law. Roger dimly viewed a future civil war.

Sittingbourne was fading behind them now. It was getting dark, and they hadn’t stopped to eat. Jack suggested they rest the horses.

"In Faversham," said Roger absently. "We’ll sup there, too."

A light snow began to fall. Roger thought of Kit. He’d hoped for much from Kit. His excellent mind. . .if only he’d been able to concentrate. Damaged. . .was he, too, threatened with death? Roger stared out northeast at the snowy banks of Faversham Creek and the marshes, spreading into the Swale – a house or two, some rooks in the giant overcast bowl of sky. He forced his thoughts to settle on the days ahead. His last will was ready. He’d see Liza and his friends and his trustee in Canterbury. He’d find a way to talk to Kate. And at Chalk Church next Sunday, he’d have his Day in Court. Mori Mihi Lucrum! It could have been worse.

The two riders supped at the old Flower de Luce in Faversham, then trotted off toward home. Darkness meant nothing to them – only ten miles to Stephen’s, as Roger called it – but the snow fell fast, and when they came up the drive to the big lighted house in its pure white garden, it looked strangely like heaven.

Roger was expected here; he’d sent word that he was excused from December Jail Delivery and would be home early. Lady Manwood had gone up to bed but Ned of the stable was there to take care of the horses, and there was a good fire and roast beef in the kitchen.

On Monday Roger stayed home to dine with Liza and his cousin John Boys and told them he had to go back to London before the end of this week, but he’d surely be home for the holidays.

"Well," said Liza, "take the coach; riding out in this weather you’ll catch your death o’cold."

Roger agreed.

Lady Manwood noticed her husband ate and drank very little. When he refused his sack, she lifted her eyebrows and peered at him. "Archdeacon Redman sent his man yesterday, asking you to come for an interview. And something odd – he said you should bring along your will."

"Tomorrow," said Roger. "Or Tuesday."

It was Tuesday morning when Roger alone rode into Canterbury and found William Redman in his study, and there the two men talked.

First about place and time. "At Shorne," said Roger briskly. "On the fourteenth, early. Let’s say, ten minutes past midnight. That’s acceptable to Lopes. I have a note from him."

Redman, a soft-spoken, owl-eyed, pudgy man, was annoyed. This was not what he’d expected. "One would think a proper place would be St. Stephen’s and a proper time, more graceful in conceit, after the holy days."

Roger reminded him: "I’ve been given thirty days’ grace from the end of November. Twelfth Night would be well past my deadline, you might say. Can’t see it would be a bother. . ."

"Indeed – not a bit selfish? To expect me to make a trip all the way to Shorne at the start of my busiest season?" Redman sighed. "I have duties at Bishopsbourne and at Upper Hardres. . .But since her Majesty has granted you this privilege of choice, m’Lord Chief Baron, so be it. And now for the will."

Roger spread the neatly written pages on the table, and Redman put round spectacles over his round eyes to scan the script silently for a couple of minutes. "No," he said slowly. "No, this is not the mood we want. Too worldly by far. I’ve written a few bits we can insert." He pulled a page from a cubbyhole in his desk.

Roger perused the sanctimonious passages of praise for the Anglican establishment and bristled: "William, this is a legal document, not a bloody sermon." 3

The archdeacon quietly took the paper and laid it on the table. He looked into Manwood’s eyes and smiled. "Sir Roger, you don’t wish your kin to be attainted, surely, and you do wish your bequests properly attested to here, and everything in its place properly transferred to your heirs and assigns?"

They stared at each other.

"You do believe in God?"

"I believe in the good Lord. . ."

"Then no worry," said the archdeacon hastily. "Now let’s go through this. It occurs to me you won’t be needing your new black stallion."

"He’s yours. Just say he’s one you gave me. And after that, let me add something else – about remembrances. We can write these changes as notes and interlinings and your man can copy it all out fairly. I may have to go back to Shorne before he’s finished, so let’s say I’ll sign it with witness when you come to Shorne – in about a week, right?"

Redman was dubious. "The archbishop will find such arrangement irregular."

Roger chuckled. "Venerable sir – surely you’re capable of discerning that this whole wicked farce is irregular. Oh, there’s a certain Senecan – Lucanian precedent, but nothing like it in any law of England."

Redman pressed his lips together and took up his pen. "About remembrances?" 4

"Put down, ‘I give to every of my wife, my son Hart and his wife [that’s my daughter Anne], my sons-in-law Sir John Leveson and Robert Honneywood, my cousins John Boys, Edward Peake and Stephen Teobald, one ring of gold worth four marks with mine arms and this inscription – or circumscription – of words and letters:’ "

Roger took the pen and made the letters in bold capitals:

MORI MIHI LUCRUM. R.M.

Redman reclaimed the pen. "And what else to your wife?"

"Well, she said to me this morning, ‘if you’ll be altering the will, do something for me and change that part about the rents.’ She doesn’t want to mess with them. But that’ll come later. This part can stand: ‘to my well-beloved wife, beside her yearly living hereinafter mentioned, I will all the household stuff, jewels and plate, which she brought at her marriage, and more, that which since by my privatie is appointed to be worn and used by her and remaining at my house at Great Bartholomew’s London, other than the great tapestry hangings appointed for the great dining chamber [they’re new] and for my own lodging chamber at Great Bartholomew’s. . .’ "

"No, no," said Redman, "Great Saint Bartholomew’s, wheresoever it occurs here."

Roger shrugged. " ‘And the great Turkish carpet, and the great velvet cushions embroidered with my arms. And she nevertheless to have the use of the same and of the household stuff at Shorne, so long as she liveth my widow, and to her also two coachhorses and eight other of my geldings, in the opinion of more part of my executors thought meet for her, together with saddles, pillions and bridles – and other furniture thought to be meet for the same: and all the stocks of sheep, kine and other cattle [for her] to the hands of my nephew Rafe Coppinger, farmer at Stoke, and over that, to her five hundred marks. . .one moiety within two months after my death, and the rest within twelve months. All which moveable goods to her absolutely given, I know, are better worth than one thousand pounds by year which with five hundred pounds by year and better in living, as hereafter is mentioned, I trust will be accounted a good portion for my wife, to her good contentation.’ "

Redman, tired of writing, handed the pen to Roger, and they went on patching and re-doing. It appeared that Roger’s wife and her step-son Peter were not fond of each other – so Roger settled lands on Liza west and north of Rochester, " ‘and to my son Peter during her life to have his dwelling and living by east of Rochester, about Stephen’s [I write it Stephen’s] and Canterbury and east Kent – Sandwich, Romney Marsh, Thanet and elsewhere. And so they to dwell separately if they list not to keep house together.’ "

Then Roger bequeathed a third spread of lands, south of the Stour, to cousins and nephews.

So Medway and Stour divided dower properties of Roger’s first wife (Doll Teobald, Peter’s mother) and Roger’s second (Elizabeth Coppinger Wilkins), and the Stour also served as northern border for other relatives’ lands. Later Kit may have thought of Roger’s will when he wrote in I Henry IV, III, i., "The Archdeacon hath divided it / Into three limits very equally." Instead of Medway and Stour, Glendower, Mortimer and Percy were dividing by Severn and Trent, and Glendower says, "There will be a world of water shed / Upon the parting of your wives and you."

In his will Roger left money to provide work and wages for the able-bodied poor of St. Stephen’s, and for the hospital there. These were not ribbons-to-heaven bequests; all his life Roger had made useful gifts of time and money. He’d seen an act through Parliament to provide for perpetual upkeep of Rochester Bridge; he’d started and endowed the Roger Manwood Grammar School in Sandwich; served as one of the original governors of the Queen’s Grammar School at Lewisham, where his wife’s cousin Coppinger was rector. He’d built a new House of Correction at Westgate, Canterbury, and erected seven almshouses at St. Stephen’s, with four pounds a year for each person who lived there, for bread, fuel and extra.

Now in his will he left small annuities to his longtime servants, and outside it he left standing various private trusts he would put in the hands of his son-in-law executor Sir John Leveson and his lawyer-cousin John Boys.

After putting finishing touches on the document, Roger and Archdeacon William shook hands and said goodbye.

"Frescobaldi II is yours, as of this hour," said Roger. "He’s in the stable behind Chambers, saddled and bridled. But use him with care, sir, for he’s bright, and not mild-mannered."

-----------------------------

It was late in the day when Manwood left the cathedral precincts, on foot, walking slowly through Christchurch Gate and down Mercery Lane.

There was the Marley house across the way. John’s drawbridge-style counter onto the street was closed against winter weather, but he was visible through the window, sitting close to it, trimming a sole. Roger started toward Westgate, then turned back and stood a few seconds on the worn stoop of the shop door before knocking.

A darkly handsome girl about twenty years old opened the door and stood in the vestibule, smiling; behind her stood a tall redheaded youth about her own age. For an instant Roger thought he was dreaming and Kate Arthur-Marley stood there, a young woman again. But it was Kate’s daughter. She recognized him and asked him to step into the shop, where John rose from his work with a greeting. The young couple disappeared into the kitchen, where Kate must have been cooking – essence of ginger and baking bread came floating into the shop.

John wiped his hands on a piece of rag and shook hands with Roger. "Wanting a new pair of boots for the holidays, counsellor? Sit down – sit down."

"Not right now." Roger shook his red wig and stood there awkwardly. He wasn’t sure what he was wanting. "Have you seen Christopher lately?" he asked, looking strangely vacant.

John’s eyes narrowed. "He came here in September with a play he wrote – it played at the Chequers. He stayed home away into November and then went to London. Seems to live a worried life, your honor – doesn’t talk a lot about his business. Awfully thin. . ."

Kate appeared in the doorway. She made it glow: slim, even in her apron imperious, her big eyes shining: "His honor the Judge! Home early! Welcome! Put up your horse around back and stay for a drink!"

But Roger looked so uncomfortable she knew something was wrong.

"I stopped in to ask a favor. Ah – up at my place on Gad’s Hill, Wednesday week – I’m having a bit of surgery done. Nothing serious – a minor procedure. I don’t want to bother my son Peter or my lady about it – haven’t told them – but I’ll be needing extra help in the house there for a few days. Someone sensible to keep a watch of the fires – to cook good things, manage washing and sending things upstairs. . ."

"A housekeeper."

"A housekeeper," Roger said gratefully.

Kate laughed. "If one of us went, old Jack Fisher’s nose would be out of joint."

"Not if it was you, Kate. You’d be a proper helper – he’s told me himself he thinks you keep the best rooming house in Canterbury." Roger turned to John. "Would you let her go? I’ll be taking the coach up Friday with Fisher. She could come along – get the house warmed up and something going in the kitchen. I’m preaching a sermon Sunday, and I’ll need to work on it all day Saturday."

John put-by his trimmed leather sole and slipped his sharp knife into a scabbard. "Surgery on Wednesday, eh?"

"Wednesday night, yes. The doctor and surgeon are coming from London. They may stay over – it should be finished by Thursday."

"But then," said John, "you’ll need more care afterward than before, won’t you?" He slipped his leather apron off over his head. "Wish I could come too, but these next weeks I have more orders than I can manage. Maybe Nan. . ."

Roger wanted to say Kate alone would be just right, but he kept still.

"Stay for a slice of cake," said John, seeing something like fear in Manwood’s face. "We’ll talk it over."

It was agreed Kate should go; the coach would wait outside Westgate for her at dawn Friday – no, make it Thursday. Yes, she’d be back safely for Christmas.

Roger shook hands all around, muffled up and strode along through Westgate toward Stephen’s – in his cloak pocket, a jar of blackberry jam sealed with wax.

-----------------------------

In the Gad’s Hill house on Friday Roger told Kate what was going to happen. She was taking linens down to the wash house, and he walked up to her on the landing, and told her.

She said, "I’d guessed something like. But why not home, with your lady wife? She’ll feel awful, counsellor, that you didn’t tell her."

"Couldn’t do it. It would bother her. Remember when Edmund Coppinger went under – you know – and now this a-top of it – well, if she knew, she might speak out in anger, before the day, and then she’d be imprisoned. This way it’ll look more natural."

Kate nodded, her eyes filled with tears. "Doll, now – Doll you could have told."

"Doll was different."

"You’ll see her in heaven." Kate started down the last flight of steps with the laundry, and Roger stopped her, embracing her hips.

"There’s no marriage in heaven."

"So, counsellor – " Kate’s eyes looked straight ahead – "you shall lie in Abraham’s bosom."

"Better, ma’am, in Arthur’s bosom."

Shaking a little, she turned to him, and he led her to his lodging chamber. They went in and closed the door.

-----------------------------

The tenth of December dawned damp and chilly. Fog was lifting off Higham Marsh as the rough old bells in the neighboring church towers sounded, calling the faithful to morning prayer, and very soon afterward, it seemed, came time for the main Sunday service.

Curious about Manwood’s upcoming sermon at Chalk Church, the parishioners, along with the invited congregations of Lilly, Stoke, Hoo and Shorne, pressed into the little stone building. They came wrapped in fine winter woolens, carrying laprobes and hot bricks in their warming-pans – pans they wouldn’t need after the narrow room was packed with warm humanity. There were Pages, Brookes, Chenys, Coppingers, Wilkinses, a Mendes, a pair of Lucies and some Druries. Roger’s son-in-law John Leveson came over from Whorne’s Place with a couple of Warwickshire cousins. Kate was there, in her bonnet, with Jack Fisher. Pews were shared with visitors and all settled down expectantly.

After gospel, epistle and collect, Roger, introduced by the minister, climbed up into the vicar’s stall and silence fell.

His eyes searching the room for old acquaintances, he shuffled his notes and began, his voice deep and clear:

"Friends, neighbors, Kentishmen – lend me your ears!"

A ripple of laughter at the old joke.

"This is not a funeral – Oldcastle was buried a hundred and seventy-five years ago this coming Thursday – that is, they buried bits of bone and ash of him, left from the fire that roasted him to death.

"The evil that men do lives after them; the good oft is interred with their bones. But today, so close to the anniversary of his sacrifice, let us honor his life – celebrate the good that was in that stubborn man."

At this moment clouds parted outside and sunlight came streaming through the three tall narrow windows behind Roger, casting a halo around his crazy red wig, silhouetting his elegant doublet – he wore no surplice. Kate thought he must look like some inspired prophet from the Holy Land.

Roger went on: "Oldcastle has been my light on many dark occasions, for however maligned, he was a brave man. My text today is Timothy Two, Chapter one, verse seven: ‘For the Lord hath not given us the spirit of fear, but of power, and of love, and of a sound mind.’

"What have you all heard of Sir John? He was an Englishman of Welsh descent who worked for the government of Henry IV and was a close friend of the king’s son, Prince Hal.

"Throughout his life, Oldcastle was obsessed by the idea that no other power should take precedence over his country’s ruler and its laws – not the pope of Rome or his archbishops in England – and this belief led him to help create the law of praemunire. He became a follower of Wycliffe and spread about ideas of church reformation – lollard ideas. And then he married Joan Cobham and came here to live at Cooling. Known as John the Chaplain, he became a lay-preacher, speaking in favor of honesty and simplicity in church government – preaching from the pulpits of Hoo, Halstow and his wife’s churches.

"He declared confession was good for the soul but it needn’t be made to a priest; that a man could go on pilgrimage and still be damned, or stay home and still be saved; that images were aides to the memories of the unlearned, to bring to mind the sufferings of Jesus and the good deeds of the saints; images were not to be idols. He said he’d believe what a truly holy church decreed but denied that the pope, cardinals and prelates had power to determine such things.

"In 1410 the pope heard of Sir John’s teachings and put the churches of Hoo, Halstow and Cooling under interdict – so then Sir John came here to Chalk to preach. Standing where I’m standing, he declared we should seek absolution only from the good Lord and our own consciences. Here behind me," Roger turned, "a little door was cut in the wall, so if the inquisitors came in the front door during service he could duck out. See, this low window used to be the door." (There was some craning of necks from the pews.) "See how it’s been cemented around here?"

"Well, he asked his friend Prince Hal to support him, but the prince was embarrassed and turned away, and Oldcastle, disgraced, went on preaching. When Hal became Henry V, he condemned Sir John as a heretic. Oldcastle, I’m sure you know, escaped to Wales, but he was caught in December 1417 and brought to London, where his conviction was upheld and he was drawn on a hurdle to Giles’ Fields, and there, on the fourteenth of December, hanged in chains, he was roasted to death. All because he would not bow to some very ignorant pronouncements of popes and prelates."

Roger now began to speak his own mind: "Today the church still needs reform. You know, I’m sure, of the ministers of the word now imprisoned by the archbishop of Canterbury. If any good comes to those prisoners through the providence of God and the gracious clemency of her Majesty, the inquisitors won’t be responsible for it. For indeed, in this one point they’re of my mind, in thinking that reformation cannot come to our church without blood, and that no blood can handsomely be spilt in that cause unless the inquisitors themselves be the butchers and the horse-leeches to draw it out.

"But tell them this from me: that we fear not the men who can but kill the body. We fear the Lord, who can cast both body and soul into unquenchable fire. And tell them also this: that the more blood the church loseth the more life and blood it gets. When the fearful sentence pronounced against the persecutors of truth is finally executed upon them, I’d gladly know whether they who go about to shed our blood or we whose blood cryeth for vengeance against them, shall have the worst end of the staff. We are sure to possess our souls in everlasting peace whensoever we leave this earthly tabernacle.

"And good friends, I would not have thee discouraged by this recent persecution of honest ministers. Reason not from the quick success of things to the goodness of the cause. If, in beholding the state of the Low Countries and France, you would have so reasoned, you might easily have given the holy religion of God the slip twenty years ago!

"Look at it straight: let the prelates prove the lawfulness of their places rather than exercising by force their unlawful tyranny.

"What do they get by their tyranny, anyway, seeing it’s truth and not violence that most upholds their places? Do they not know that the more violence they use, the more breath they spend? And what wisdom were this, trowe ye, for a man that had coursed himself windless, to attempt to recover his breath by running up and down to find air? He might soon have as much life in his members as these Lord Bishops have religion and conscience in their proceedings."

His audience smiled, but was he winning or losing them? He went on:

"The whole issue of their force and bloodthirsty attempts doth witness against them that they are the children of those fathers who never as yet durst abide to have their proceedings examined by the word, and methinks they should be ashamed to have it recorded unto ages to come that they have shunned to maintain their cause, either by open disputation or by any other sound conference or writing.

"Let me be overthrown by rational disputation, and I here publicly protest I’ll never molest Lord Bishops again while I live, but will with very great vehemency maintain them and their cause, as ever I did oppugn the same. Otherwise, I’ll never leave the displaying of their proceedings till they be made so odious in our church and commonwealth that all sorts will think them unworthy to be harbored therein.

"They may quench their thirst with my blood if they will, provided they be able to make their cause good, by the word of God. But if I overthrow them – as I make no question of it, if they dare abide the push – " and here Roger took a deep breath and thundered out the next words – "then they to truss up and be packing to ROME, and to trouble our church no longer!"

Discreet murmurs of dismay and approbation came from the pews.

"Though their bloodthirsty proceedings be inexcusable, the manner of their proceedings is just as intolerable. First: they may twist an examination any way they will – for who can stop them when they be sole judges and sole witness themselves, and no other present but the poor examinate? The seat of justice they commonly use in these cases is some close chamber at Lambeth or some obscure gallery in London palace, where in accord with an evil conscience that feareth the light, they may juggle and foist in what they list without controlment, and so attempt (if they will) to induce the party examined to be of a conspiracy with them to pull the crown off her Majesty’s head."

Here Roger extended his arms in exhortation, and his listeners sat very still. "I put case, friends. If they should do so (as here you see is a way laid open to them, to broach any conspiracy in the world) what remedy should the party that stands there alone have, by appeaching or complaining? None other than this: ‘He lies like a puritan knave’; ‘I’ll have his ears’; ‘I’ll have the scandalum magnatum against him, for he has slandered the high commission and the president of her Majesty’s council’ – namely, my Lord of Canterbury’s worship. And here behold the poor man’s reward.

"Second: You must lay your hand on the book and not know whereunto you must be sworn. Yea, they will compel you to accuse yourself, or else you shall lie by it – which ungodly practice, savoring so rankly of the Spanish Inquisition, is flat contrary to all humanity, the express laws of our land and the doctrine of our church. For the law is so far from compelling any to appeach himself in a cause wherein life, goods or good name is called in question, that it – our own English law – condemneth as oppressors of the common liberty of her Majesty’s subjects, and as wresters of good order of justice, all those that will urge or require any such unreasonable thing – as appears in a plain statute of the 25th of Henry VIII."

Roger was teaching law to a puzzled but attentive congregation. He paused, and then leaning out over the edge of the pulpit he said quietly, "Friends, whether these matters be not worthy the consideration of the gravest counsellors in the land, I leave to the judgement of every true Englishman that loves his Prince and the liberty of his country. Let us pray."

Knees were bent and heads bowed as Father Lawrence led the closing prayer and the recessional. Outside on the old church porch – the stone carving of Puck and the magic monster laughing over their heads — Father Lawrence and Manwood bade farewell to the congregation. Some parishioners were smiling, some were obviously disturbed. The people dispersed more quietly than usual, going around back to find their mounts and carriages and straggling down Church Lane to the Dover Road.

-----------------------------

The gallows-speech over, 5 Roger and John Leveson climbed Gad’s Hill together on foot and in silence, savoring the crisp air and the scudding clouds. Leveson knew what was in the wind. After all, he’d suffered through the deaths of Mildmay, Walsingham, Randolph. Roger was the last of the big ones.

They hiked past the cedars. Leveson had it in his mind to tell Roger’s son Peter about what was coming – the young man would want to be there.

"How much of the sermon do you think they absorbed?" Roger asked his son-in-law.

"They like you, Roger – they respect you. A good deal of it, I’d say. There were many sympathetic."

Roger stopped for breath. "You know, Jack, you and I are knighted servants of her Majesty – they call us ‘sir’ – yet I can’t help feeling – do you get that feeling? – that au fond they think of us as a couple of camel-herders."

"Amen!"

A step or two more, and Roger repeated the big word: "Amen!"

-----------------------------

On Tuesday Archdeacon Redman appeared at Roger’s Gad’s Hill house with a request: "Could you reconsider and make it today instead of Wednesday night? I'm needed Thursday at Bishopsbourne."

Roger was astonished. "Be practical, William. The arrangements are for Wednesday night. Lopes is saving time for me then; he’s bringing Fernando Álvarez as his surgeon, and there’ll be a couple of my friends – by appointment, you understand, not extemporé. Sorry."

"Very well," said Redman, miffed. "I brought the will. We mought as well get it signed."

"That we can do." Jack Fisher was called up to Roger’s study to be first witness, and after a last reading (Roger noticed an insertion which he let stand – a modest bequest to the archdeaconry of Canterbury), signatures were affixed and the document sealed.

Redman slipped the pages into his briefcase and studied Roger’s grim jaw and stony eyes before addressing him, very gently: "You must not think yourself wronged by your deservèd penalty, counsellor, for you are to willful blame, and you have put his grace the archbishop quite beside his patience. True, you’ll need courage to pay your debt with blood – " Redman’s voice quavered a little, but he pressed ahead with his obviously prepared speech: "but you can’t deny you’ve displayed defect of manners and of government: pride, haughtiness, opinion and disdain – and this, haunting you, loses men’s hearts and leaves behind a stain upon the beauty of all parts, besides beguiling them of commendation." His lips snapped shut and he stood stiffly, determined not to lapse into sympathy for the condemned man.

"Thanks for this lesson," said Roger, smiling. "Come on down to the kitchen now, you and your boy, to sup with us there."

-----------------------------

Wednesday the thirteenth dawned dark and gloomy. The archdeacon slept late and Roger did his best to keep things bustling below stairs, for Kate was showing a tendency to tears which puzzled the other help. There was much scrubbing and polishing, and clean sheets and pillow-shams were put on the big bed in Roger’s lodging chamber. Later, he and Kate stole a private hour locked in his study, with difficulty avoiding interruption by William Redman, who stalked the corridors burdened by his role of Nemesis.

Kate had to attend the cooking of the evening meal. She fed all but Roger, who’d already gone up to bed, saying he wasn’t hungry. After supper was over and darkness fell, she went to the back door to see the night sky – there were no stars – and to watch for the black coach, which very soon turned in at the gate, its lanterns glowing, and came to a stop in the cobbled courtyard. Two swarthy spectacled men – doctor and surgeon – climbed down and reached back for black bags and several basins which glinted in the light of the cresset beside the stable door. Fisher was there to welcome these men; Kate turned and climbed the kitchen stair.

Later still a lathered horse clattered to a sudden halt in the court. Its rider, tall, wrapped in a well-cut travel-worn cloak, pulled off his gloves, tipped the hostler, and after a short exchange of words entered the house and climbed the stair. He was Robert Poley, come as backup for the archdeacon. He’d returned from Scotland on the twelfth and received instruction from Whitgift to ride to Shorne and return on the fourteenth with news of Manwood’s death. 6

The kitchen boy climbed up with him to point out Roger’s chamber door. When Poley entered, he saw the doctors already at work. Their patient, wearing a red nightshirt and his wild wig, lay in bed propped up by several pillows. Kate stood at his right, biting her lip, and John Leveson and Peter Manwood watched from a vantage point near, but not in front of, the small fireplace. It was a cold night and the fire had been built to maximum size. Redman, praying, was stationed at the foot of the bed, while the physician and surgeon closely observed a stream of blood flowing from Roger’s left arm into a steel basin. All but the medical men looked at Poley in surprise as he closed the door behind him and leaned on it, nodding casually to the assembly. "Reporter for his grace the archbishop," he said gently.

Roger’s eyes focused on Poley. "Where’s Christopher?" The usually deep voice was gone, and the words came out high-pitched and querulous. "Have you seen him?"

"No, your honor. He’s at Baynard’s Castle with Lady Mary Herbert, writing entertainments for the court."

"When I need him."

"He knows nothing of this matter, counsellor. Nobody knows but the archbishop, Burghley, her Majesty – perhaps the Lord Oxford. . ."

"And we, gathered here."

"And we, gathered here."

"Where’s Ned, eh? When I need him."

"At Hackney, your honor. Ever since he left Julia Arthur’s place…"

Kate’s eyes flashed. "And she dead of the shock of it!"

"…he’s kept at home in Hackney."

"He’s friends again with Christopher?"

"No, counsellor. He hates Marley and you, too, sir. I heard he melted your chain."

"He’s melting me, Poley – all because he believes a lie."

Redman, whose prayer had been interrupted by this conversation, spoke up: "Not at all, your honor. You suffer not for any personal misunderstandings. No social connection, no temporal intervention from any highly-placed person could save you. You must expiate your fault before heaven, and tonight’s procedure is the start of that. We’re doing a great favor, m’Lord Chief Baron, for your immortal soul."

Roger, his face contorted, sat up, causing consternation among his attendants. Redman turned and left the room.

"Be calm," said Lopes, pressing Manwood down again onto his pillows.

Roger sighed and looked around vaguely. "There’s a veil, a film, coming over everything in the chamber. There are big fishhooks in it, pointing at me."

Leveson stepped forward. Taking a small vial from his jacket pocket, he consulted the physician in a low voice.

Lopes took the tiny bottle and offered it to Roger. "Sir John has brought narcotic principle of opium."

Roger downed the stuff gratefully and lay back, eyes closed. The blood flowed, silence filled the chamber. Across the room Leveson contributed a muttered Hebrew supplication.

"Sailors," said Roger, in his new voice. "Sailors laughing, their shirts unbuttoned, bottles in their hands. And here come the dancing maidens – bona robas – bona robas – clothed only in their long, long, long black tresses." He opened his eyes. "Bonny Kate Arthur – stay with me. You better pray. I’m cold, Kate. Legs like stones. Get another blanket, Kate."

She did. The surgeon took two basins of blood to the door. Poley took them downstairs to be emptied.

Roger spoke again, softly now, and Kate leaned down to hear. "Green fields, green fields of thyme. Can ye not smell ‘em? And choughs – and Danish gulls, Kate."

Two more basins were filled. The bell on Shorne church tower clanged midnight. Dr. Lopes checked his fat pocket watch. "Turn over, man," he said harshly, suddenly, rolling Roger on the bed. The man took a long, long scalpel from the surgeon’s bag and thrust it deep into Roger’s colon, cutting, slashing, with a fierce laugh. Peter leaned against Leveson and slipped to the floor unconscious.

Feces and blood spread over Roger’s pale legs and the bed. He opened his eyes, muttered something to Kate, and died.

The doctor put his hand on Roger’s back, felt his wrist – waited. And then: "Gone." He opened the door and said to Redman and Poley, who stood in the corridor: "No pulse – there’s no pulse. Try it yourself." And while the surgeon rinsed the scalpels, Lopes set about packing up.

Poley did take hold of Roger’s pale wrist for several seconds, and then with "Good night all," he was off. They heard him loping down the stairs.

The medical team followed, bowing to the archdeacon, who had re-entered the chamber and now stood awkwardly immobile, his black shoes planted on the Anatolian rug in the middle of the room, his eyes fixed on the mutilated corpse.

Leveson spoke in Hebrew over the inert form and then, supporting Peter, half-dragged the young man out the door. Kate started rebuilding the fire.

Redman seemed stuck there. He wiped his spectacles and regarded the woman. "The fire should be banked, Mistress Marley, the chamber made cold. I understand the body’s to be moved to St. Stephen’s first thing."

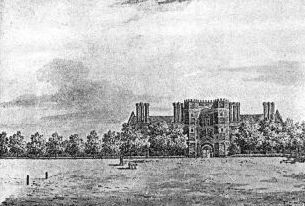

|

| Roger Manwood's Place House at St. Stephen's |

She walked to the head of the bed and stood there, militant. "The coach leaves before dawn, to reach Stephens soon after noontime."

Redman pressed his lips into invisibility, then opened them, distaste permeating his words. "I know. He wished – all of them wish – for the Angel Gabriel to lift their souls before the death-day is over. Stupid superstition!"

"He’ll rest in Abraham’s bosom, while you must deal with your own bad dreams, sir."

For several seconds they stared at each other, hostility vibrating – and then Kate pushed up her sleeves, tightened her jaw, and slowly bared her white teeth.

Horrified, realizing he was about to be physically attacked, Redman rushed from the room, leaving Kate to weep alone.

1. Sir Thomas Gresham and Archbishop Parker as Roger's friends – see his DNB, pp. 991-992, and Edward Foss. The Judges of England. AMS Press 1966, Chapter Five. Back

2. Convicted two Flemings of anabaptism. DNB, Manwood, p. 992. Back

3. Sanctimonious passages of praise. Lewis Grant writes that since Redman was in control, "we have a very pious version of Sir Roger's regard for the Anglican Church." (Lewis J.M. Grant. Christopher Marlowe, the Ghost-Writer of all the Plays and Poems of Shakespeare. Part 2. Orillia, Ontario, Canada: Stubley Press, 1970, p. 212.) Back

4. The parts of the will included in my text are culled from valuable excerpts offered by Lewis Grant, ibid., pp. 211-216. My own persistent search for this document so far has proved fruitless. Mr. Grant has also seen the connection between Sir Roger's bequests to a divided family and Act III of Henry IV. Back

5. Much of Roger's sermon is taken from his last Marprelate booklet, The Protestation. The Marprelate Tracts are available in facsimile from The Scolar Press Limited. 93 Hunslet Road, Leeds 10, England. Back

6. Poley had returned from Scotland. Eugenie de Kalb, RES. Jan. 1933: "Robert Poley's Movements as a Messenger of the Court, 1588 to 1601," p. 16. Back

For Christopher Marlowe's comments on the execution of Roger Manwood, see his anagrams in Henry VI Part I (First Folio of Shakespeare), Henry VI Part II (First Folio of Shakespeare), and The Taming of the Shrew (First Folio of Shakespeare).

Other chapters:

The Home page of Roberta Ballantine's site dedicated to Christopher Marlowe

Contents of Roberta Ballantine's site dedicated to Christopher Marlowe